Greenland is the world's largest island and represents one of the greatest

untapped resources in the Northern Hemisphere. There is enough fresh water

tied up in the Greenland ice cap to raise the sea level 18 feet if melted.

The abundant natural resources have hardly been mapped let alone exploited

in this extreme environment. The Arctic Circle cuts through the bottom

fifth of the island leaving four fifths of Greenland in the dark for most

of the winter and in light most of the Summer. My first views of Greenland

were from the seat of an airline on the way to Europe, as they are for

most Americans who see Greenland. If you fly from the West Coast of America

the shortest route is the Polar Route because of a spherical Earth. Denmark

owns Greenland so to fly to Kangerllussuaq most flights depart from Copenhagen.

This means you get to fly over Greenland twice on your way in and twice

on your way out, if you are coming from the West Coast of America. If

it is summer you will probably have light regardless of the time of day.

If you are lucky enough to have no or little cloud cover then you may

see expansive ice sheets leading to a miniature wonderland of snow shrouded

mountains which seem like so many fingers holding the ice cap in a giant

bowl. The immense weight of the ice cap, which is over 10,000 feet thick

in places, actually pushes down the center of the island almost 1000 feet.

If you happen to be there between June and August, you will see huge emerald

blue lakes on top of the ice cap. This is due to the continuous summer

sun and warmer ambient temperatures melting the surface ice. In the Midnight

Sun these lakes on the ice begin to overflow and run off the domed ice

cap, melting canyons in the ice. These ice canyons course along the surface

toward the edge of the icecap for miles until the water finds a crevasse

or crack in the ice. These crevasses are caused by movement of the glacier

over the rough strata that lies beneath 3000 feet of ice near the edge

of the icecap. When the water finds these cracks in the ice it goes straight

down melting huge holes in the ice the French explorers call "Moulins".

When Fall comes and the temperatures drop, these canyons freeze and eventually

get covered by cornices of snow blown into place by ferocious winter winds.

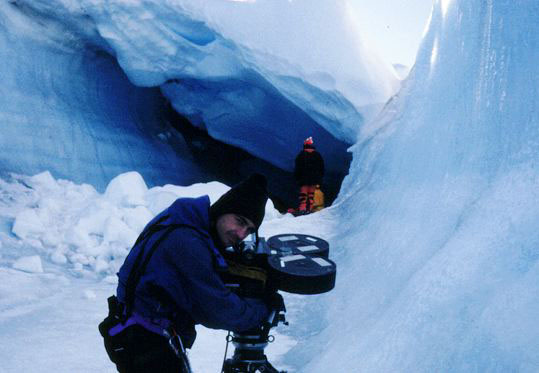

This creates horizontal ice caves like the one above. We shot the IMAX

film "Journey Into Amazing Caves" with MacGillivray Freeman

Films in the Fall of 1998. The water stopped flowing in late September

and we were able to descend almost 600 feet straight down into these holes.

Due to the extreme pressure and the plastic nature of ice under pressure

the bottom of the moulin we were in was closing very quickly, making the

time we spent there extremely dangerous. The weight of the ice above at

that depth was almost 20 atmospheres or about 300 psi. The expedition

leader Janot Lamberton had seen ice boulders burst from the wall like

cannon shot and ten foot spears of ice break loose near the surface which

could be traveling close to 100 miles per hour by the time they reached

us. For one of the sequences my brother Michael and I had to rappel almost

600 feet down into one of these moulins. He and I set up the camera on

a chock block of ice weighing several tons. Jammed into the wall between

two fins of ice this giant block of ice seemed to be protected from above

by an overhang. Michael started turning a backup ice screw into the wall

between the ice fins when suddenly a crack shot 40 feet up the wall. It

all happened with a loud crack that sounded like a rifle shot in the confined

space and the whole ice block started to roll out of its position. We

had already secured the 50 pound IMAX camera to the 10 foot diameter ice

block with screws. We knew if the block rolled out of it's perch it would

land in the water at the bottom and turn upside down with the camera acting

as an anchor. We were both roped to the camera on short lines so if we

didn't get crushed in the fall we would be held under the block and drowned

unless we could disconnect from the camera in the 32 degree water.

When we felt the block shudder we looked at each other in shock then quickly

disconnected ourselves from the camera and block and tied into the secure

screw in the wall, hoping that if the block did roll out it would leave

us hanging above the water. Over the next two hours we shot several shots

of the expedition team rappelling down to water level, and ascending back

toward the surface. Every couple of minutes we would feel the block shudder

beneath us as it was slowly crushed. There are few moments in life that

compare to the way we felt when at last we were standing back at the surface

again with all our equipment and some of the most incredible images I

have ever had the privilege to shoot.

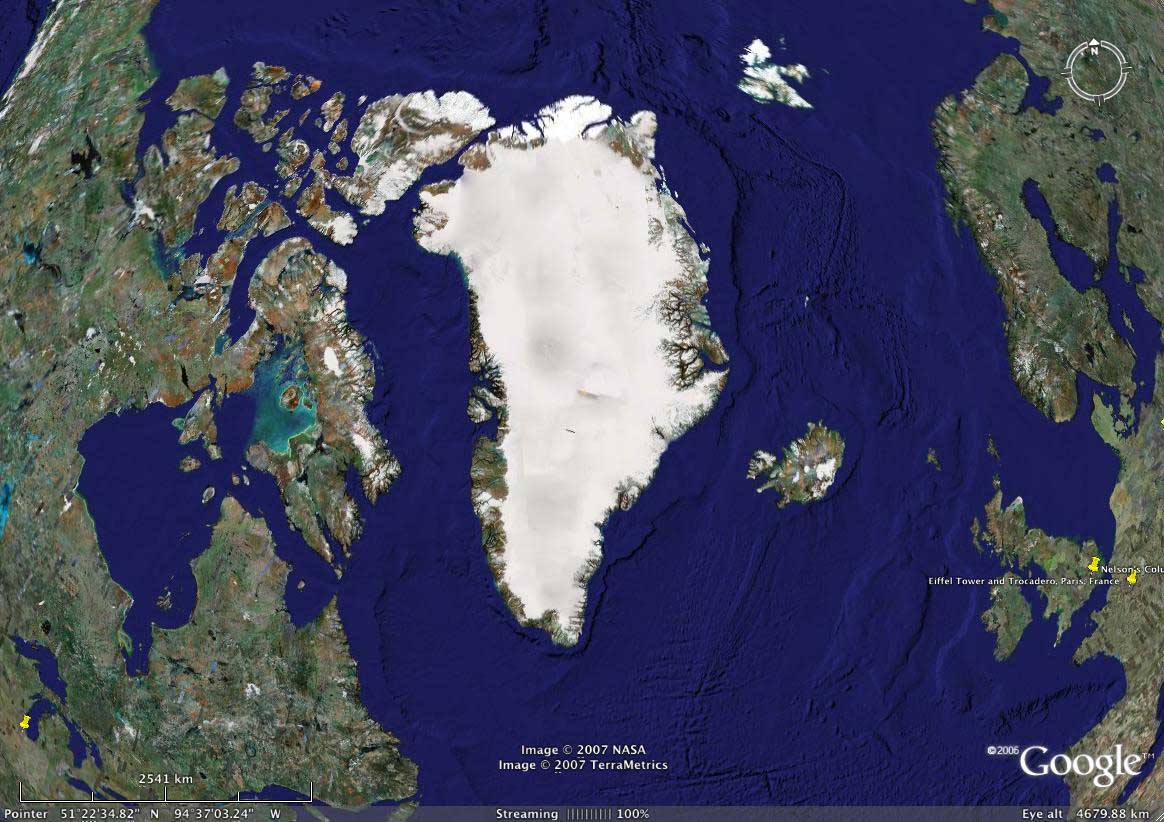

Greenland in relation to other landmasses. The usual view most of us are familiar with is from a Mercator projection, a view which stretches the image to straighten the lines of longitude making the top of Greenland appear much wider at the top than it really is. Above is the Google direct view. Chicago is the pin on the bottom left. Paris is the pin on the bottom right, with Spain and Morocco being the bottom land masses. Svalbard is the snow covered island group to the right on top. Iceland is directly right of the lower main body of Greenland.

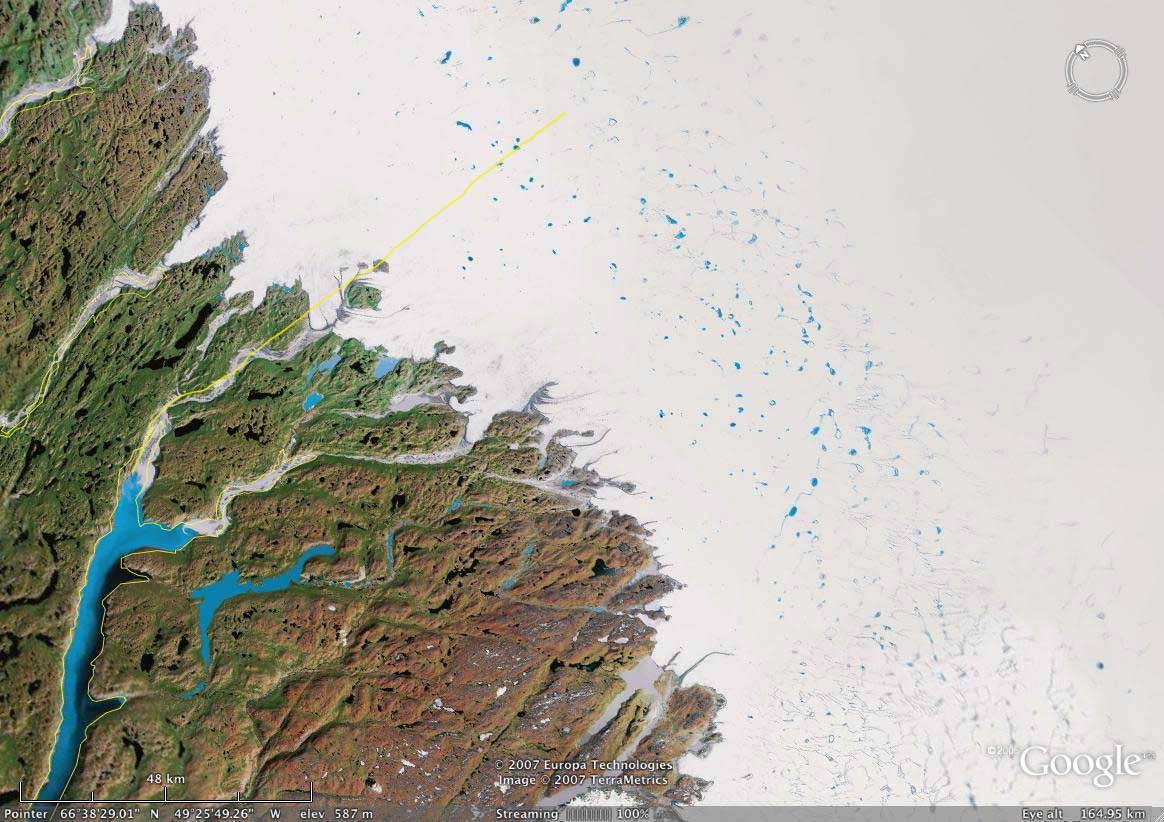

The yellow line shows the route we took from Kangerlusuak to the area of Moulins thought to have the most promise by Janot Lamberton and his team. We flew up to the icecap in a big Sikorski 74 that carried our crew of 12 and 3000 lbs. of gear.

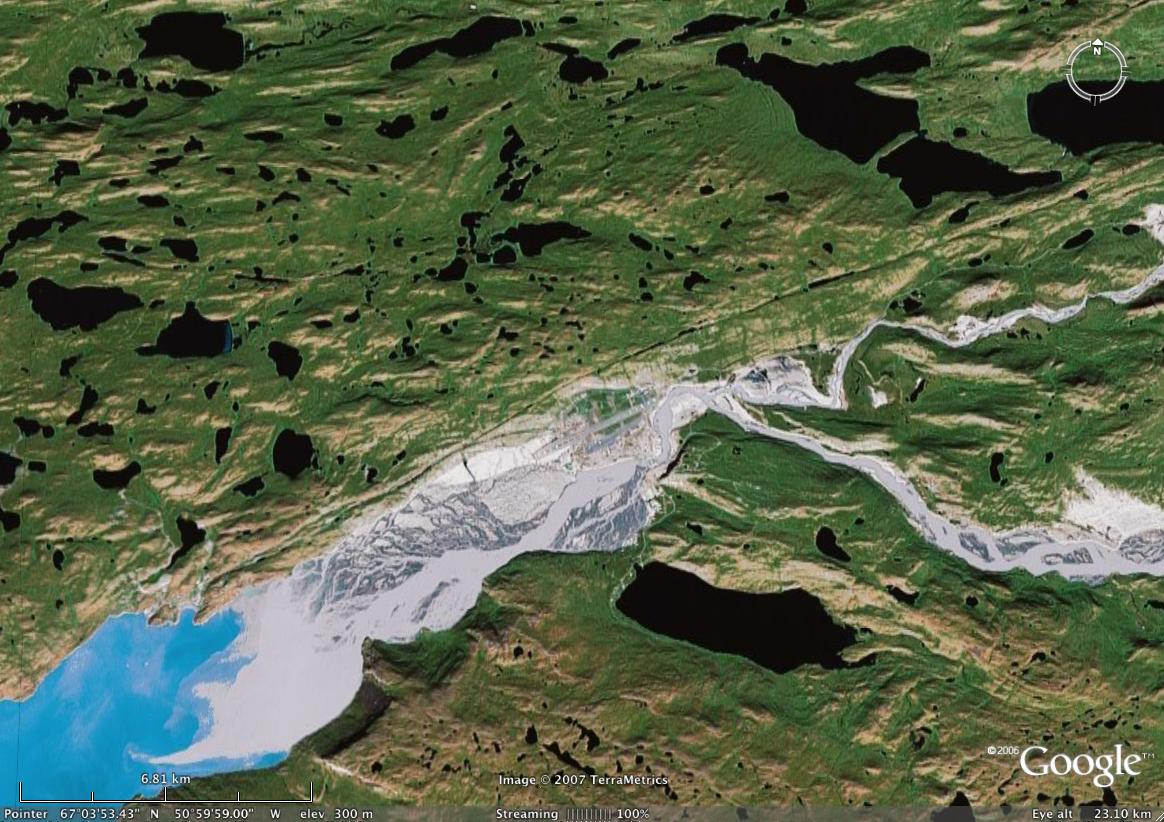

This area is where the crew flew into and is one of the larger settlements in Greenland. If you look closely at the center of the frame you can see the airstrip, which is capable of accommodating commercial aircraft. All of the lakes you see here are set in seemingly endless tundra, dotted with herds of musk ox and Arctic wildlife including fox and polar or "ice" bear as the Greenlanders and Europeans call them. With the absence of prey on the Icecap there was little threat to the crew from these amazing predators.

|

|

|

In 1998 while returning from shooting a commercial in San Diego I stopped to see Greg MacGillivray at MacGillivray Freeman Films in Laguna Beach. I had worked on a film on the Yampa in Colorado with Greg as kayaking talent, some of my first work in front of the camera as well as doing mount shots from my kayak. This meeting with Greg in Laguna led to his asking me to direct photography on an IMAX film to be called "Journey Into Amazing Caves". In August of that year I found myself flying over Greenland on my way to Copenhagen where I would board a plain to fly back to the very area I was flying over. We were just above the Arctic Circle so it was light as we flew over at 9:00 pm. I found myself straining to see through the window of the jet exactly where we would be working. As near as I could tell our flight path was directly over the area where the French team was supposed to be already setting up camp. Instead what I saw was a network of turquoise veins running across the ice from terminus points they wound their was East splitting into branches that snaked for miles to large blue lakes on the middle of the icecap. I had no idea until seeing "An Inconvenient Truth" just how significant these runnels could become! The turquoise blue is either water over ice on the glaciers or as a result of "glacial milk" over land from rock ground so fine by the glaciers that it stays in suspension. You can see this dissipate as it mixes with the salt water in the fjord leading from the terminus to the open sea. I would encourage you to go download Google Earth so you can explore. If you don't already have it, this tool changes everything about the way you view and explore the World.

Previous years ice canyons interrupted by moulins in this season leaving "dry canyons" sculpted in the ice.

Gordo with IMAX Mark II 65mm IMAX Camera in an extinct canyon with a winter wind and snow formed cornice in the background.

Looking down into the "Moulin" from one of our camera positions.

Dangerous horizontal ice caves lead to extinct moulins from years past.

Raging rivers in the ice get bigger every year as the climate heats up.

|